A sovereign debt crisis occurs when a country is unable to meet its obligations to repay its creditors. Generally speaking, a country facing default would look to take one or more of these steps (depending on the conditions its creditors would agree to):

- restructure the debt;

- extend maturity;

- reduce coupon payments;

- increase grace periods; and sometimes

- seek full or partial debt forgiveness from its creditors.

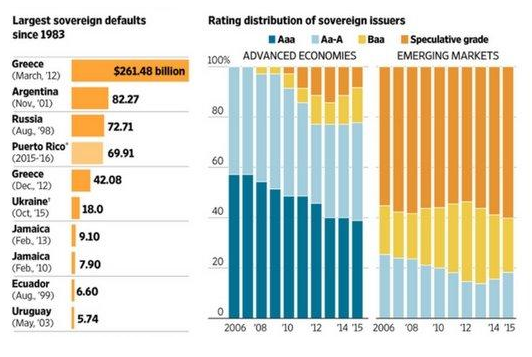

A recent WSJ article looked at the increase of defaults in the world and prospects in the future given the increased borrowing by countries to fuel growth and inflation. The saving grace might be the low/negative rates of the new debt though.

Deadbeat Nations

Seven years after the global financial crisis, big government defaults still occur and the outlook isn’t much better.

Source: Moody’s Investors Service

With the return to rising interest rates in the U.S., the economic slowdown in China and large debt taken on by many nations during the cheap money era, sovereign debt defaults have become a growing concern for investors. In this article, we highlight a few key thoughts on this complex topic and present data that suggests a debt disaster is not looming on the horizon.

History of sovereign debt crisis:

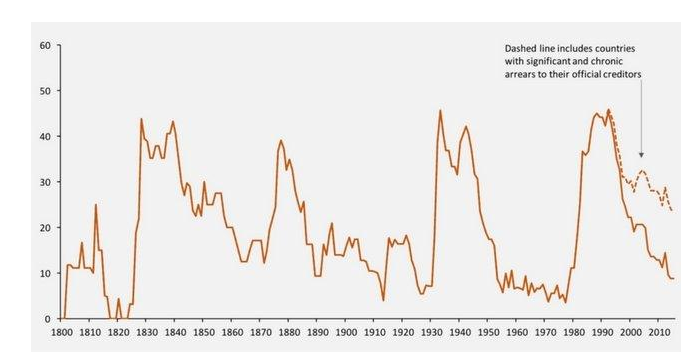

This time isn’t different Sovereign debt crises have happened multiple times and in many countries throughout history. Reinhart and Rogoff’s chart shows the ebb and flow of defaults from 1800 to the present. A Federal Reserve paper documents a total of 250 sovereign defaults by 106 countries between 1820 and 2004. France defaulted on its sovereign debt eight times between 1500 and 1800, while Spain defaulted thirteen times between 1500 and 1900. Sovereign defaults are scary, but despite what investors might think, history reveals that defaults are a fairly common occurrence.

Default Waves

Percentage of countries in external default or restructuring, 1800-2015

Sources: Reinhart and Rogoff (2009), Beers and Nadeau (2015), and Reinhart and Trebesch (2015).

How do sovereign debt crises happen?

Generally, when countries start spending more than they earn from tax revenues, government debt levels can rise and become unsustainable. Subsequently, creditors and investors can lose confidence in the government, doubting the borrowing country’s ability to repay the loan, and the once “risk-free” government debt becomes viewed as risky. In order for countries to get out of a debt crisis and regain the coveted reputation of being “risk-free borrowers,” troubled countries must implement “credible and tangible fiscal and structural reforms.”

Among the developed nations, Greece is a prime example of both this downward spiral as well as a path back to solvency. Conditional bailouts by the EU have helped Greece recover from its sovereign debt crisis. In January 2016, Standard & Poors upgraded Greece’s credit rating from CCC+ to a B- rating, citing Greece’s compliance with cost cutting measures and Greece’s economy showing more resilience than expected as reason for upgrading Greece’s rating status.

The most recent debt crisis occurred in Europe. While the US subprime and housing crisis started as a local problem, it quickly snowballed into the European debt crisis. European banks that were highly exposed to US housing loans went bust, resulting in the European Sovereign Debt crisis.

In a December 2015 research article for investment professionals, analysts at Goldman Sachs believe there’s a current risk of some emerging market countries defaulting on their debt due to:

- US raising rates;

- China’s slowing growth; and

- falling energy prices.

Countries who have high trading volumes with emerging market countries or other economic exposure to emerging markets may be ones to look out for.

Which countries are considered risky today?

In July 2015, Business Insider identified 24 countries that are currently in government external debt crisis: Armenia, Belize, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, The Gambia, Greece, Grenada, Ireland, Jamaica, Lebanon, Macedonia, the Marshall Islands, Montenegro, Portugal, Spain, Sri Lanka, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Tunisia, Ukraine, Sudan and Zimbabwe. The article also reported that 13 countries are at high risk for government external debt crisis: Bhutan, Cape Verde, Dominica, Ethiopia, Ghana, Laos, Mauritania, Mongolia, Mozambique, Samoa, São Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Tanzania, and Uganda.

While the list of nations currently in default or at risk of default is long, these countries collectively do not account for a significant percentage of the world’s GDP or world consumption.

Are banking crises and sovereign debt crises one and the same?

Generally speaking, yes. Banking crises and sovereign debt crises typically go hand-in-hand as a nation’s bank usually reflects the health of a country’s lending system. A banking crisis usually precedes a coming sovereign debt crisis. Banking crises such as Ireland experienced in 2008 and Spain endured in 2012 show how “liquidity and solvency troubles of the banking sector can radically turn into a fiscal burden sufficiently large to lead into a sovereign debt crisis….”

How can countries avoid a Sovereign Debt Crisis?

Typically, when trouble arises, governments make changes to their fiscal policies and its central banks step up to offer recapitalizations (rearranging their debt), asset relief programs, liquidity measures, etc., to stave off default and restore confidence. According to the St. Louis Federal Reserve, during the European Sovereign Debt Crisis, many different forms of state aid were approved by EU member nations from 2008 to 2012. In total, these debt relief measures added up to about 5 trillion euros – about 35% of the European Union’s total GDP for 2011.

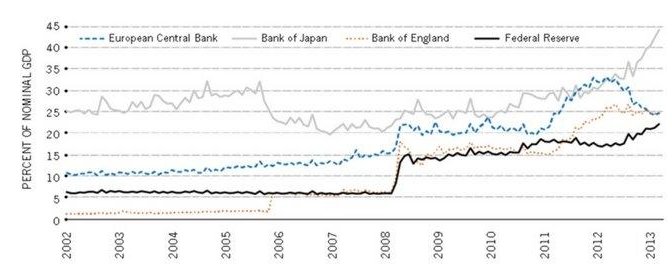

Size of International Bank Balance Sheets

Just as defaults are common, bailouts like the ones we saw in Europe during the global financial crisis are prevalent across the globe. The Federal Reserve charted the size of International Central Bank Balance sheets relative to the balance sheets of the US Federal Reserve rose dramatically as it printed money to buy bonds and flood the banking system with money for lending.

Similarly, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of Japan all grew their balance sheets significantly over this same period. While these large debts are what worry many investors, the chart shows that all this increase in money supply has had its intended effect:

- increasing liquidity;

- promoting lending (loans to households and non-financial corporations), and thereby;

- fostering growth in their respective economies.

Loans to Households and Non-Financial Corportaions

Source: Fed, ECB, BoJ, BIS. As of 30 Jun 15

What’s the likely impact of these ballooning balance sheets?

As countries borrow large amounts of money to jumpstart their economies, their increasing debt obligations raise concern about the government’s ability to meet their future debt payments. Following the financial crisis, the low interest rates in many economies across the world prompted many countries, companies and individuals to go on a “debt binge,” pushing out the due date on ballooning balance sheet problem. Many nations effectively “kicked the can down the road” for future generations to pay. In order to meet these future debt obligations, their economies must grow.

Investors today appear to be worried that current economic conditions – including the current drop in energy prices, the economic slowdown in China, and upswing in US interest rates – may impair the ability of many smaller nations which borrowed money at low (negative) rates to repay their burgeoning debts, causing sovereign debt crises to emerge on a global scale. Indeed, the speed with which European crisis of “the PIIGS” (collectively, Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain) blew up definitely gives us reason to pause and carefully consider today’s risks.

More recently, we’ve seen the 2016 default by Puerto Rico, preceded by Greece’s default last year. While Puerto Rico is a US territory, not a sovereign nation, Greece is an advanced economy and an EU member that failed to make its payments. The strong US dollar and the devaluing of several emerging market currencies appear to have further raised the risks of default among emerging market economies.

While concerns over emerging market economies is understandable, some investors are concerned that countries in the developing world – especially the US and Japan – won’t be able to fully meet their debt obligations and a default (or perhaps even a potential default) might trigger a debt crisis among these global economies and create havoc in the markets. We address these fears next.

We’re not worried about U.S. defaulting on its debt even though U.S. debt has ballooned The main reason for our conviction is our currency – the “almighty” US dollar.

The dollar continues to have a firm grip on its status as a safe haven for investors. As crises develop elsewhere, its value among investors is elevated even more. The US government always has the fallback option of printing more money to pay its debt as the dollar’s value seems undiminished in the global economy. The dollar continues to hold credibility in the world.

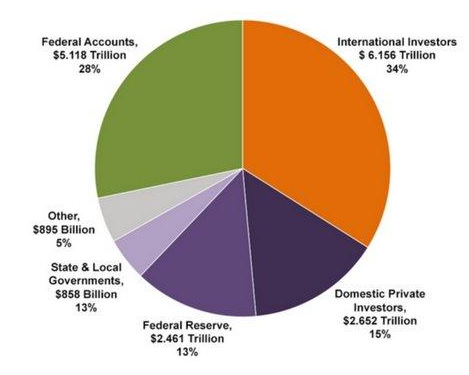

We owe a significant portion of our debt to ourselves and foreign debt holders.

The only way such a colossal default would be possible would be if the US dollar experienced a massive devaluation, spiraling the world economies into a colossal economic depression. Such a scenario likely would make the Great Depression seem like a mere ripple by comparison. As no deb tholders would want to risk such a global economic cataclysm, credit likely would be extended, in near perpetuity if need be – and thus the game continues.

Who deos the US Government owe money to

($18.1 trillion in federal debt, as of December 2014)

Source: OMB, National Priorities Project

US debt is still considered a safe haven.

Despite investor concerns, US Treasury debt remains one of the most liquid and active markets in the world. Governments, corporations and individuals around the world buy US debt as a safe place to invest large amounts of capital. US debt may not be risk free, but given the alternatives, it remains a top choice for many investors.

Defaulting on US debt is arguably unconstitutional.

Article I, Section 8, Clause 2 of the US Constitution states, “The Congress shall have Power to…borrow money on the credit of the United States….”

Further, Section 4 of the 14th Amendment reads, “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned.”

Why Japan is not Greece – despite its high debt-to-GDP ratio According to Forbes, among advanced economies, Japan is the debt champion, with a debt/GDP ratio over 180%. Troubled Greece comes in second place with a debt/GDP ratio just under 150%, and Italy holds third place at 109%. By contrast, the US is in eleventh place (out of 34) with debt equal to 61% of GDP. So with this high debt ratio, why is Japan not defaulting as Greece has done? Many reasons, including: The majority of Japanese debt is held by Japan itself.

The biggest holders of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) are some of Japan’s largest corporations and banks. Even when the underlying fundamentals of the economy don’t make sense, Japan’s companies and individuals continue to buy Japanese bonds – not missing even one year. And even when JGBs were issued at negative rates, demand has persisted.

Think about that for a moment. Negative rates mean that buyers not only receive no income, they actually suffer a reduction in principal for borrowing – yet the Japanese have still been willing buyers. Unless this long loyalty streak is broken, it seems that Japan could inflate its way out of its debt problems by using the simple expedient of selling more bonds (printing more money). Greece, on the other hand, does not have the luxury of escaping its debt problems in a similar fashion.The yen is strong.

The demand for Japanese currency is akin to the demand for the US dollar in the world. As long as the yen has perceived value to investors, Japan will have the ability to print more yen and inflate its way out of its debt balances.

International coalitions are being created to deal with government defaults. An article by the nonprofit Project Syndicate highlights the steps now being taken by countries and organizations to:

- streamline guidelines;

- create a framework to avoid defaults; and

- be better equipped to deal with sovereign defaults.

In September 2015, the United Nations decided to implement procedures to be used to help restructure debt of troubled nations, effectively creating a system for mitigating massive debt restructuring problems. Though they don’t have the force of international law, these steps were designed with the hope that they would be universally followed.

The International Capital Market Association (ICMA), with the support of the IMF and the US Treasury, has suggested changing the language of debt contracts such that restructuring of debt could be approved by a super majority of creditors, thus preventing one or two creditors from stalemating attempts to restructure a country’s sovereign debt.

While we may create international rules and put systems in place, the ultimate responsibility for avoiding debt crises lies with individual countries. Countries need to practice fiscal responsibility and international bodies need to respect sovereign immunity, rather than encouraging countries to exchange their sovereignty for short-term gains promised by better financing conditions or other rewards. As stated in a Columbia University article, “A system that actually resolves sovereign-debt crises must be based on principles that maximize the size of the pie and ensure that it is distributed fairly. We now have the international community’s commitment to the principles; we just have to build the system.”

Portfolio implications: Some views from the money managers we recommend We spoke at length with some of the money managers we recommend about their views on the likelihood of widespread sovereign defaults, and generally their views were as follows:

Global growth and inflation have moved lower, yet downside risks persist.

While the spread between Emerging Market and Develop Market yields have reached 2008 crisis levels, manager consensus is that EM debt is challenging. They advise investors to be cautious and underweight near term but not abandon EM debt over the long term as they believe EM debt still has the thrust for stronger growth, better demographics and generally lower debt loads.

Spread Betweeen Local Currency EM & DM Sovereign Yields

Accommodative monetary policy remains crucial for ongoing global recovery.

The managers we recommend believe it may be necessary for the ECB to intervene to stop a sovereign debt crisis (as seen on March 10, 2016 when Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank, lowered interest rates and expanded the ECB’s bond buying program). Alternatively, the Fed could intervene to stop a financial crisis in order to prevent widespread chaos. ECB support is needed to nudge growth and inflation such that the EU economies don’t slip into recession. The expansionary policy in Japan is also needed to anchor inflation.

Based on our conversations with a number of managers, they believe that global banks will need to continue expansionary policies in the coming years.Active management is critical in such an environment.

The managers we recommend acknowledge that risks remain and investors should:

- maintain portfolios with ample liquidity (bond ETFs may not be as liquid);

- manage risk exposure;

- avoid chasing markets for yields;

- maintain liquidity to react to market dislocations; and

- stay diversified.

The managers we recommend emphasize that risk assessment is the key to making investment choices.

As one manager explained in 2011:

A robust approach to the assessment of sovereign risk has become even more essential. It also means that investors must assess risk of one issuer relative to another. Some factors are more important than others – including maturity profile, domestic/foreign ownership balance, issuer credibility and general financial depth. Many of these opportunities are slow-moving in nature; in the short term, liquidity and volatility will continue to provide the early warning signs for investors.

In practice, today’s environment requires investors to be more discerning about their investment choices. For example, although EM debt is challenging as a whole, India may be a good buy as it has benefited most from the falling commodity prices. (Note: This is an example and is not intended as an investment recommendation.) We believe that investing with active managers, rather than passive ETFs, gives investors a better chance of making these fine distinctions.

Predictions are not reality.

In 2010-2012, the European sovereign debt crisis threatened the existence of the Euro and European Union. Then the ECB stepped in. With the crisis averted, countries like Spain and Portugal have started growing again. The Euro still exists, and Greece is still a member of the EU. This shows that concerns of widespread defaults might be exaggerated, even while we acknowledge the existence of downside risks.

SUMMARY

Some of the active bond managers we recommend, including Western Asset, Goldman Sachs, PIMCO and GW&K, are large bond managers actively investing in the heart of the fixed income market. Collectively, they’re monitoring trends, comparing yields and employing risk measures to construct portfolios that avoid excessive risk, limit illiquidity and reduce concentration.

There are daunting risks for investors that warrant caution. However, according to history and current data, the risks of massive sovereign defaults may be overstated.

In short, it’s not different this time.

THANK YOU JOYN. ARTICLE POSTED PREVIOUSLY:

https://joynadvisors.com/sovereign-debt-crisis/

Disclosures and Disclaimers:

The information provided herein is for general educational and entertainment purposes only, and should not be considered an individualized recommendation or personalized investment or financial advice; nor should the information provided herein be considered legal, tax, accounting, counseling or therapeutic advice of any kind. Any examples or characters mentioned herein are hypothetical in nature, purely fictitious, and do not reflect any actual persons living or dead. Practical Investment Consulting makes no representations, whether express or implied, as to any expected outcome based on any of the information presented herein. Users assume all responsibilities or the use of these materials, including the responsibility of protecting the privacy of their responses. Practical Investment Consulting does not accept any liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect or consequential damages or losses arising from any use of this document or its contents.

This material is intended for the personal use of the intended recipient(s) only and may not be disseminated or reproduced without the express written permission of Practical Investment Consulting.